Historical examples of hot sectors that didn’t end well

All throughout history there are examples of once hot market segments that have captivated investors, only to eventually crash back down to earth in a ball of flames. The most important thing to know is that, in each case, the investors who participated in these bubbles all claimed that “this time it’s different.” It is easy to get caught up in a market frenzy. It might even be easy to rationalize it. But the truth is, bubbles will always exist, created through the nexus of excess liquidity and the irrational exuberance derived from investor emotions. And bubbles burst. They always do. It is simply a matter of when, not if. The examples below illustrate just how dangerous they are, and how much pain their eventual crash caused.

The Dot-Com Bubble

In the early 2000s, the technology sector, especially companies focused on the internet, faced a monumental collapse known as the Dot-Com Bubble. This period witnessed a staggering decline, where the NASDAQ Composite index plummeted by nearly 78% from its peak.

exibit 1

Exhibit 1 clearly demonstrates the rapid rise, and equally rapid fall of the Nasdaq Index.

Several factors contributed to this dramatic crash. Many tech companies were vastly overvalued, despite generating minimal or no profits. Investors, caught up in speculative excitement, poured money into these stocks without considering their actual financial health. Numerous firms operated with unsustainable business models, relying heavily on investor capital to support operations.

As reality set in, the market underwent a severe correction, triggering a massive sell-off and bringing the bubble to a bursting point. This episode provided valuable lessons for investors and regulators alike.

One critical lesson was the importance of valuation. Investing in stocks based solely on their speculative future growth, without solid financial fundamentals, proved unsustainable. It became clear that focusing on a company’s intrinsic value–its revenue, profit margins, and cash flow–were crucial to avoiding such speculative traps.

Furthermore, the Dot-Com Bubble underscored the necessity of conducting thorough due diligence before investing. Investors learned to critically assess business models, management quality, and competitive advantages, rather than blindly following market trends or hype.

The crash also highlighted the significance of sustainable business models. Companies must demonstrate a clear path to profitability to justify high valuations. Those relying solely on continuous funding without showing how they would eventually become profitable faced severe repercussions. Additionally, market sentiment and psychology played pivotal roles in the bubble’s formation, as well as its eventual demise. Understanding investor psychology and market dynamics is essential for recognizing and mitigating the risks of speculative bubbles. It is from this period that the concept of “irrational exuberance” emerged.

Lack of regulatory oversight was also cited as a crucial takeaway. The Dot-Com Bubble exposed gaps in regulatory frameworks, prompting calls for better accounting practices and financial disclosures to provide transparency which would ultimately protect investors.

Many investors also chose to ignore the power of diversification by overconcentrating their portfolios in tech stocks, resulting in significant losses. A diversified portfolio helps manage risk during both market and sector-specific downturns. This led to a deeper appreciation of the benefits of effective risk management. Investors learned the importance of managing and limiting exposure to high-risk investments in order to safeguard their portfolios. Taking a long-term perspective became essential for navigating market volatility and avoiding short-term speculative traps. Investors learned to resist the allure of chasing quick gains based on market fads, focusing instead on sustainable growth prospects.

Moreover, the crash emphasized the fundamental importance of corporate earnings and profitability. Companies must generate sustainable profits, not just revenue and website visitors, if they intend to maintain long-term viability and justify their market valuations.

Lastly, the Dot-Com Bubble highlighted the transformative potential of technology while cautioning that not every technological innovation guarantees profitability (think pets.com). Evaluating the practical applications and market demand for new technologies is crucial for assessing their long-term impact and profitability in investment decisions.

The Great Financial Crisis

During the years 2007 to 2008, the global financial sector faced a monumental collapse known as the Great Financial Crisis. This crisis shook the foundations of banking and finance worldwide, leading to the severe downturn of major financial institutions and necessitating large-scale government interventions to stabilize the economy.

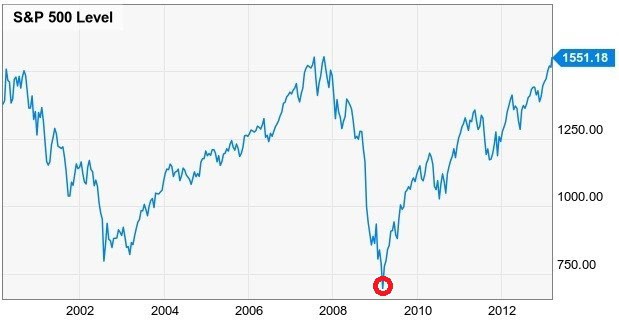

exibit 2

Exhibit 2 illustrates the precipitous decline in the broader market, as defined by the S&P 500 Index.

The primary trigger was the subprime mortgage crisis, where banks issued mortgages to borrowers with poor credit histories. As many of these borrowers defaulted on their loans, it triggered a domino effect of financial instability. Compounding this issue were complex financial products like mortgage-backed securities (MBS) and collateralized debt obligations (CDOs), which spread the risk across the financial system, making it difficult to manage and assess.

Banks and financial institutions were heavily leveraged, meaning they borrowed significant amounts of money to invest in these risky assets. When the housing market collapsed, the value of these investments plummeted, causing massive losses that were beyond their capacity to absorb. This led to a credit crunch, where liquidity froze as banks became unwilling, or unable to, lend to each other and to businesses, exacerbating the crisis further.

Once again, several important lessons were learned from this crisis, one of which was the concept of systemic risk. The interconnectedness of financial institutions highlighted common (systemic) risks that could threaten the entire financial system. Regulators and financial institutions recognized the need to better understand and manage these complex interdependencies to prevent widespread failures.

The crisis underscored the essential role of liquidity in maintaining financial stability. Banks learned the importance of holding sufficient liquid assets (eg: cash and equivalents) to meet short-term obligations and withstand financial shocks and strong regulatory oversight became imperative to curb excessive risk-taking and ensure financial stability. The crisis prompted regulatory reforms such as the Dodd-Frank Act, aimed at increasing transparency, accountability, and oversight in financial markets. Financial institutions revamped their risk management practices, implementing rigorous stress testing and capital adequacy requirements to identify and mitigate potential risks more effectively. Transparent financial products and accurate risk disclosures became crucial for investor protection and market integrity. The crisis emphasized the need for clear information to enable informed decision-making and avoid risky investments.

From a liquidity standpoint, global central banks played a pivotal role in stabilizing financial markets through unconventional monetary policies such as quantitative easing, which injected liquidity into the economy to support recovery efforts. In addition, the crisis underscored the importance of international cooperation to enhance global financial stability. International regulatory bodies worked together to establish global standards such as Basel III, aimed at strengthening the resilience of the global banking system.

The Great Financial Crisis also bore witness to the creation of the “Too Big to Fail” paradigm. Policymakers addressed concerns about this phenomenon by imposing stricter capital requirements on large financial institutions and developing frameworks to manage their orderly resolution. It aimed to raise awareness about moral hazard, where institutions might take excessive risks with the expectation of government bailouts if those endeavors failed. Regulatory reforms aimed to strike a balance between financial stability and accountability. And finally, sustainable lending practices and rigorous borrower assessment became critical lessons learned as a result of the crisis. Preventing speculative bubbles in the housing market became a priority to avoid future financial instability

The Housing Bubble

In the mid-2000s, the housing sector in the United States experienced a devastating crash that played a pivotal role in triggering the broader Global Financial Crisis of 2007-2008. What began as a boom in housing prices quickly turned into a bust, shaking the foundations of the economy and leaving a lasting impression on both investors and policymakers.

The housing market reached its peak in 2006, marked by soaring home prices which were fueled by speculative buying and readily available credit. Lenders, eager to capitalize on the housing frenzy, relaxed lending standards and issued a significant number of subprime mortgages to borrowers with poor credit histories. These mortgages often came with adjustable interest rates that initially offered low monthly payments but would reset to higher rates after a few years, catching many homeowners off-guard and making their mortgages unaffordable.

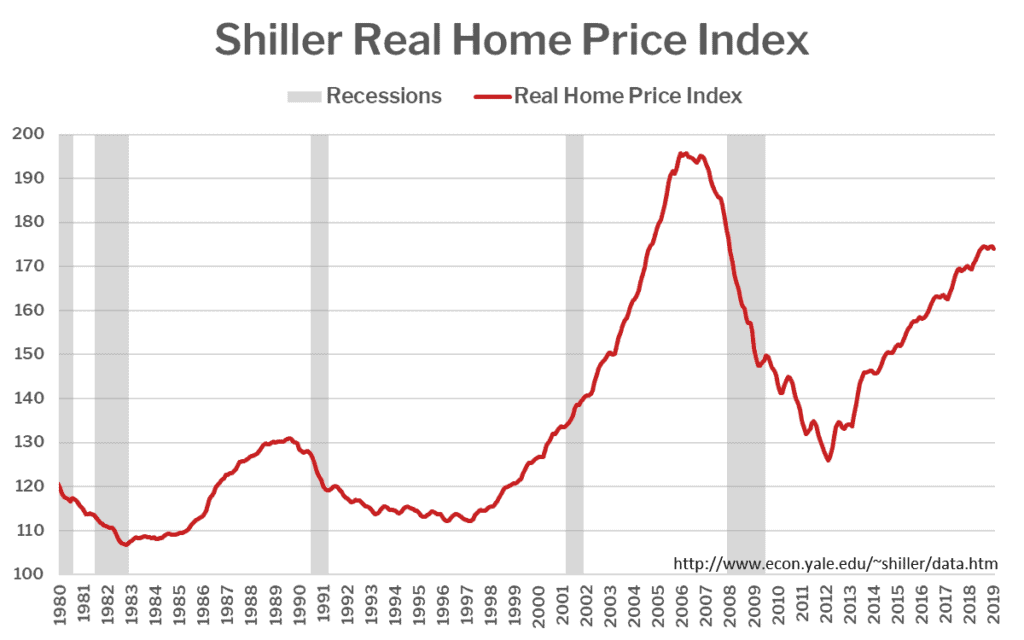

exhibit 3

In exhibit 3, the right-most gray bar highlights the rapid collapse of housing prices, after a multi-year run-up. When the market finally bottomed out in 2012, prices had returned to levels last seen in 2000, effectively erasing 12 years of gains.

To compound the issue, mortgages were bundled into complex financial products known as mortgage-backed securities (MBS) and sold to investors worldwide. These securities were perceived as safe investments due to their high credit ratings, but their true risks were often underestimated, or deliberately obfuscated. As housing prices began to decline, the value of these securities plummeted, triggering widespread panic and financial instability across global markets, ultimately resulting in a crash of the entire housing sector.

The crash was largely blamed on rapidly rising home prices, which created a speculative bubble, enticing ever more investors and homeowners to buy into the belief that prices would only continue to rise. This helped fuel the proliferation of subprime mortgages, which increased the risk of defaults among borrowers with limited creditworthiness. Additionally, the popularity of Adjustable-Rate Mortgages (ARMs) with low initial rates that subsequently reset higher led to payment shock and increased defaults. On top of that, the securitization of mortgages spread risk throughout the financial system, but the complexity and opacity of these financial products masked the underlying risks. Further exacerbating the condition was the lack of due diligence and oversight by the regulatory agencies. These factors were all compounded by the lower lending standards of financial institutions, which were known to issue loans without adequate verification of borrowers’ ability to repay, further exacerbating the risk. Ultimately it was investors’ insatiable appetite for the “easy money” promised by these highly speculative securities (e.g.: mortgage-backed securities, Collateralized Debt Obligations, and Credit Default Swaps).

The fallout from the housing crash led to profound lessons that reshaped financial practices and regulations. Both individual and institutional investors recognized the importance of diversifying portfolios across different asset classes to mitigate localized market risks. In addition, investors learned the value of due diligence when it comes to their decisions, especially with respect to complex securities whose actual structure largely remained a mystery to most investors.

The Energy Sector Crash

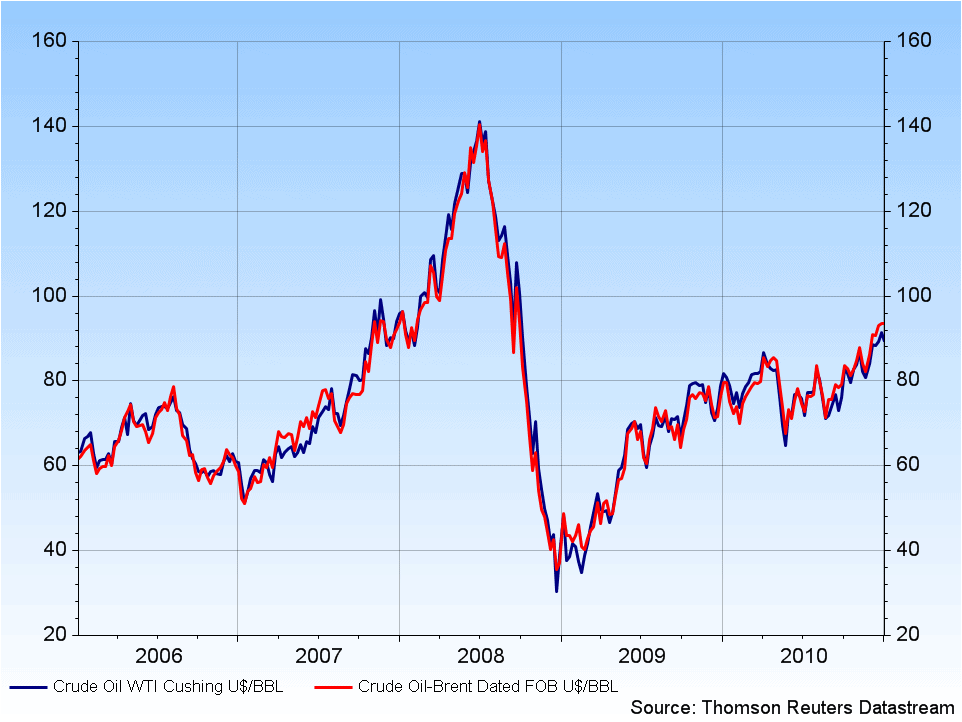

In the mid-2010s, the energy sector, particularly companies involved in oil and gas production, faced a severe crash that sent shockwaves through global markets. This period saw crude oil prices nosedive from over $100 per barrel to around $30 per barrel by early 2016, marking a dramatic decline that impacted economies worldwide. The crash had deep-rooted causes dating back several decades.

exhibit 4

The 1973 Oil Embargo by the Organization of Arab Petroleum Exporting Countries (OAPEC), a precursor to OPEC, in response to U.S. support for Israel during the Yom Kippur War, triggered a quadrupling of oil prices and caused severe shortages. This geopolitical move immediately disrupted global supply chains and sent shockwaves through economies heavily reliant on oil. Subsequent disruptions, such as the 1979 Iranian Revolution, further jolted oil markets, doubling prices and amplifying economic strains globally. Ongoing geopolitical instability in the Middle East continued to inject uncertainty into oil markets, contributing to even more volatility.

Many lessons were learned as a result of this turbulent period. For one, the crash highlighted the extreme volatility of commodity prices, especially oil. Companies and investors must anticipate and manage these rapid price fluctuations through robust financial planning and risk management strategies. Over-reliance on high prices can expose firms to significant financial stress during downturns.

And, once again, one of the main culprits was a lack of proper diversification. Spreading one’s investments within the energy sector and across different industries emerged as a critical strategy. Many investors were heavily invested in companies which were overly dependent on oil production. Investors who held positions in renewable energy sources or natural gas fared better, demonstrating the importance of portfolio diversification in mitigating the risks from oil price swings.

Of utmost importance, however, was understanding global market dynamics and geopolitical factors. Factors like increased U.S. shale production, OPEC’s strategic decisions on production levels, and shifting demand patterns from emerging markets significantly influenced oil prices. Monitoring and adapting to these broader dynamics became crucial for informed decision-making. In addition, investor sentiment and market confidence played significant roles in influencing stock prices. Adding insult to injury, negative market sentiment further amplified declines, even for fundamentally strong companies.

The Crash of the “Nifty Fifty”

In the late 1960s and early 1970s, the Nifty Fifty stocks emerged as the darlings of Wall Street—blue-chip companies like Xerox, IBM, Polaroid, and McDonald’s that were perceived as one-decision stocks: buy and hold forever. These stocks were characterized by exceptionally high price-to-earnings (P/E) ratios, reflecting investor confidence in their ability to sustain rapid growth indefinitely. The euphoria surrounding the Nifty Fifty, however, came crashing down in the early to mid-1970s, marking a pivotal lesson in market history.

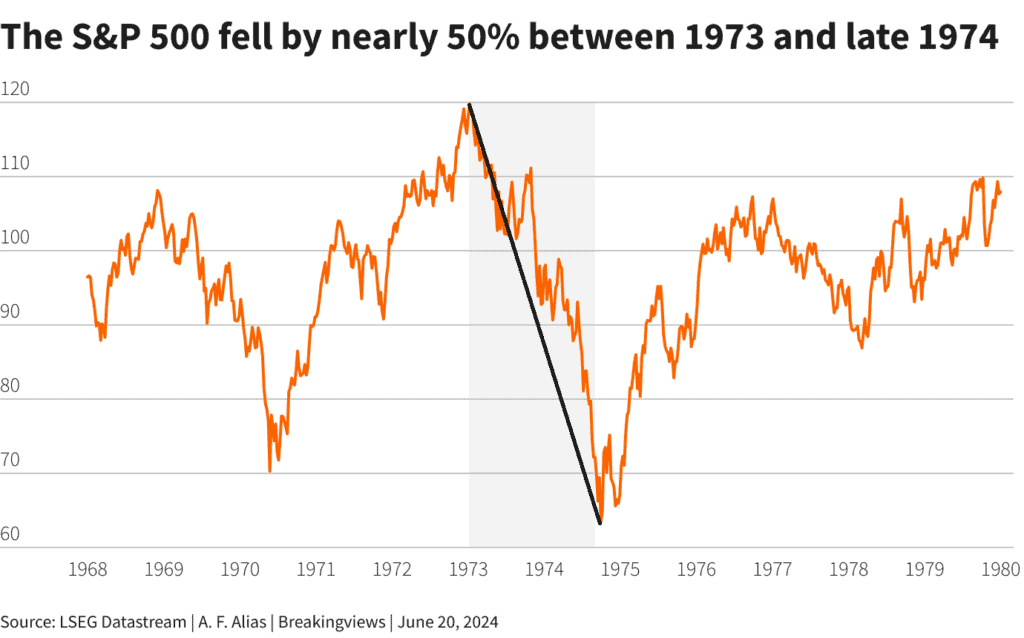

exhibit 5

The gray highlight on exhibit 5 shows the vicious decline in the entire large cap market, driven largely by the blue chip components of the Nifty Fifty. From peak to trough, these stocks plummeted by almost 50%, a remarkable decline in such a short amount of time.

The most commonly cited cause of the crash is excessive valuations. Investors bid up the prices of Nifty Fifty stocks to unsustainable levels, based more on future growth expectations than current earnings. This overvaluation set the stage for a dramatic correction when growth rates failed to meet lofty predictions. A combination of stagnation and inflation (aka stagflation) prompted a reassessment of growth prospects. As economic conditions deteriorated, corporate earnings struggled to meet optimistic forecasts, further shaking investor confidence.

To curb inflation, the Federal Reserve raised interest rates, making it more expensive for companies to borrow and invest, further exacerbating the unfavorable economic climate. This policy shift disproportionately affected high-growth stocks, which relied on accessible capital for expansion. But no factor was more impactful than the 1973 oil embargo and subsequent spike in oil prices. The oil crisis dampened consumer spending and further strained corporate earnings. The resulting economic instability reverberated through the stock market, including the Nifty Fifty. As economic realities clashed with optimistic projections, sentiment shifted from exuberance to caution. The abrupt realization that high P/E ratios were unsustainable triggered widespread selling of overvalued stocks.

The Nifty Fifty crash imparted enduring lessons that continue to shape investment strategies, even today. Paying attention to valuation became one of the most important lessons as investors realized that even high-quality companies can falter if purchased at excessively high multiples. The Nifty Fifty’s downfall underscored the importance of prudent valuation metrics and realistic growth expectations. And, of course, the value of proper portfolio diversification was cited as a contributing factor to the crash. It highlighted, once again, that concentrating investments in a handful of stocks, no matter their perceived quality, exposes portfolios to significant risk.

The Nifty Fifty crash also emphasized the benefits of taking a long-term investment perspective. Maintaining a long-term investment horizon can help navigate short-term market volatility. Investors who weathered the Nifty Fifty crash saw eventual recovery, showcasing the importance of both patience and resilience.

In summary, the Nifty Fifty crash serves as a poignant reminder of the risks associated with speculative bubbles and the importance of disciplined investing. While these companies were pillars of the business world, their stock prices succumbed to the unsustainable valuations fueled by investor exuberance. The aftermath prompted a reassessment of investment strategies, emphasizing the need for prudence, diversification, and a clear-eyed approach to valuing growth potential in the stock market.

What can we learn from the past to steer clear of portfolio pain?

The prior examples of hot sectors that crashed and burned serve as a reminder to investors that what goes up almost always comes down. Or perhaps, stated differently, the harder they come, the harder they fall. Investors could, and should, use the aforementioned examples as anecdotes by which to guide their current wealth management decisions. However, history has continually demonstrated the folly by which investors act. Developing an emotional attachment to the current “hot sector” clearly has the potential to cause severe damage to an investor’s portfolio – potentially derailing long-term wealth building objectives. The best way to avoid disaster is to strategically diversify your investments and perform periodic reviews to ensure your portfolio satisfies those objectives. Even a well-diversified investor can find him or herself overconcentrated in a hot sector that has just experienced a dramatic surge. Hopefully investors will take these lessons to heart and use them as a guide to ensure that short-term decisions do not result in long-term financial disaster.